|

Djamila Bouhired is considered by many as the most

powerful female freedom fighter of the twentieth

century, but still for vague reasons, very little is

known about this national cum international heroine. In

fact, it seems as if a veil is thrown over and around

Djamila in an attempt to obscure her name and force her

into oblivion.

Information about her part - which was quite significant

- in the Algerian Liberation Revolution consists mostly

of very irrelevant hints here and there. One could find

detailed sources of information about many less

important and less famous freedom fighters. This rises

actually more than a question about the reasons and

motives, since there is barely an Arab town that does

not have a street or a school named after this great

Algerian Woman.

Taking into consideration that she played a vital role,

even after her capture, during her trial and later on

throughout her imprisonment, in the success of the

Algerian Revolution and later on, in promoting the idea

of armed struggle against colonialism, the attempts to

ignore her are well understood. But one feels sad that

even the official departments of the country she fought

for apologize politely for the lack of any information

about Djamila, offering instead information about other

personalities. I felt so bad when an official of an

Algerian Embassy told me that the only thing they have

about this lady is that her name comes in the list of

martyrs!

The story of Djamila starts in fact in the year 1830,

when France conquered Algeria as a result of a slight,

committed by its ruler against a French envoy. The

Algerians fought bravely, but they were unarmed and

outnumbered. In the next five decades, most of their

fertile lands were confiscated and granted to French

settlers whose number reached quarter a million, while

the number of the Algerian People diminished gradually.

A few years before the break of the World War II, France

officially annexed Algeria as an African French

Province. In spite of the Algerian people refusal of the

French step, their youth were forced into military

service to fight for France during the Second World War,

the end of this war proved very bloody for the

Algerians.

Peaceful demonstrations had been taking place for some

months against the unfair treatment of Algerians (an

oft-mentioned example was the reservation of bread for

Europeans, the others only having the right to barley)

and 15,000 people had protested in the streets of

Mostaganem earlier without any incidents. But this was

to change very soon, as in response to street protests

the French Army committed a genocidal massacre at Setif.

On May 8, 1945, a day chosen by the allies to celebrate

their victory over Nazi Germany, thousands of Algerians

gathered near a mosque in Setif for a peaceful march -

for which the Authorities had given permission. It was a

market day. A few minutes later the crowd, chanting

nationalist slogans, came under fire from troops brought

in from Constantine.

The scene soon turned into a massacre - the streets and

houses being littered with dead bodies. Witnesses claim

terrible scenes, that legionnaires seized babies by

their feet and dashed their heads against rocks, that

pregnant mothers were disemboweled, that soldiers

dropped grenades down chimneys to kill the occupants of

homes, that mourners were machine gunned while taking

the dead to the cemetery.

A public record states that the European inhabitants

were so frightened by the events that they asked that

all those responsible for the protest movement should be

shot.

The carnage spread and, during the days that followed,

some 45,000 Algerians were killed. Villages were shelled

by artillery and remote hamlets were bombed with

aircraft.

A Colonel in charge of burials being criticized for

slowness told another officer: “You are killing them

faster than I can bury them.”

The Setif incident and many similar ones taught the

Algerians a very important lesson: The French would

never give them their freedom if they do not fight for

it.

Against this background, Djamila was born and raised

into a middle-class family. She was educated in a French

school but became drawn into the underground nationalist

struggle by her brother. She was at that time a very

dashing young girl with a lot of brains and rare beauty.

During the Revolution she worked as a liaison agent for

the commander Saadi Yacef.

There are also unconfirmed reports that she was at some

time in charge of armed operations in the capital,

Algeria.

The Algerian Revolution of 1954-65 was one of the most

powerful of the post-World War II anti-colonial

struggles that swept Asia and Africa. The first action

of the FLN (National Liberation Front) was a Nov. 1,

1954, guerrilla attack against French forces in the

Aurès mountains of eastern Algeria. This took place just

six months after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in

Vietnam - an event that spelled the end of French

domination of Indochina and accelerated the

disintegration of the French colonial empire.

The liberation struggle, which included armed attacks

against all aspects of the colonial regime, won

widespread support among villagers. In the cities, the

FLN quickly won solid backing. The Casbah, a

working-class district in the capital city of Algiers,

where support for the FLN ran high, became famous as a

no-go zone for the imperialist forces. Massive

pro-independence demonstrations swept Algerian cities in

1960, making clear to the French government the

determination of the Algerian people.

France threw the full weight of its modern army,

supplied with the latest weapons from NATO against this

liberation struggle. In the seven-and-a-half-year war

more than 400,000 French troops-including almost

two-thirds of the air force and half the navy- were

engaged in the war. The French also used the most

refined counterinsurgency methods. In addition to

planes, tanks, and a naval blockade, they used

electrified barriers to seal off the borders of Tunisia

and Morocco, operated dragnets to isolate the rebels,

and wiped out more than 8,000 villages in a

scorched-earth policy. They employed the most

sophisticated and diabolic methods of terror, espionage,

and torture in the attempt to smash the liberation

movement.

Casualties were extremely high. Two and a half million

people were displaced as a result of the war, and more

than a million deaths were directly attributed to it.

More than 300,000 orphaned children flooded the cities,

while 300,000 other Algerians were driven into Tunisia

and Morocco, where they became an additional base of the

liberation struggle.

Djamila Bouhired was destined to be one of those

casualties. She was captured in a raid and accused of

planting bombs responsible for many deaths in French

restaurants in Algiers. After considerable torture she

was tried, convicted and sentenced to death in July

1957.

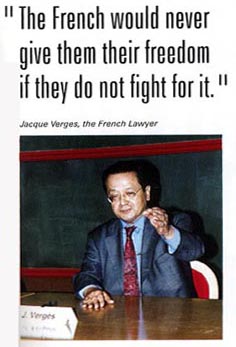

But her French lawyer, a strong believer in the right of

self-determination of peoples, was not ready to concede

defeat in the comic trial. Jacque Verges, the lawyer,

who later on won international fame for his role in

Djamila’s and other cases, waged a public relation

campaign that reached even the remotest village all over

the world. Under the overwhelming pressure of world

public opinion, the execution was postponed, and in 1958

she was sent to the prison in Rheims.

After many defeats and following huge losses of life for

both sides, the Evian Agreements were signed in May

1962, proclaiming the independence of Algeria. However,

a few months earlier, while negotiating the agreements,

France began gradually releasing the thousands of

Algerian prisoners. When Djamila was released, and

within a short period, she has married her lawyer who

embraced Islam and took the name of Mansoor.

After the independence, Djamila became the Chairwoman of

the Algerian Women Association, but she had to fight an

uphill battle for every single resolution with the then

president, Bin Bella. It took her a couple of years to

decide that enough was enough, and to leave the

political arena. She continues to live in Paris as a

devoted housewife, but at the same time, her very rare

public appearances have proved that the world still

regards her as the symbol of national liberation.

|