|

The

most famous of all travelers of the

medieval world is Marco Polo. He was a

remarkable man who ventured into unknown

distant lands. He was a man who discovered

extraordinary places on his vast journeys,

and who told the magnificent tale of his

encounters with foreign peoples and

unfamiliar cultures. But how many of us

know that another man, living and

traveling in roughly the same period of

history, had journeyed more than Marco

Polo? This man was an Arab by the name of

Ibn Battuta, the most traveled person of

his time, traveling an estimated 75,000

miles. He was also the only medieval

traveler to have seen the lands of every

Muslim ruler of his time.

On what was planned to be his Hajj trip

to Mecca, Ibn Battuta journeyed

throughout North Africa and Syria. Then

he explored the Middle East, Persia,

Mesopotamia, and Asia Minor. He traveled

to the Indian Subcontinent, spending

there nearly a decade at the palace of

the Sultan of Delhi. The Sultan

appointed him as an ambassador to China.

After about 30 years for exploring, around

the year 1350, Ibn Battuta started making

his way back to his homeland. He went back

to Fez, Morocco. There, at the court of

Sultan Abu 'Inan, he read out accounts of

his travels to Ibn Juzay who made them

into a book. This book exists today and is

known as Rihla or The Travels.

After about 30 years for exploring, around

the year 1350, Ibn Battuta started making

his way back to his homeland. He went back

to Fez, Morocco. There, at the court of

Sultan Abu 'Inan, he read out accounts of

his travels to Ibn Juzay who made them

into a book. This book exists today and is

known as Rihla or The Travels.

The Rihla told of the adventures

Ibn Battuta experienced on his travels.

Numerous times he was assaulted, once he

nearly drowned in a shipwreck; another

time he was close to being executed by a

tyrant leader. He married a number of

times and had more than one lover, which

consequently made him a father to several

children along his journeys.

The following paragraphs offer a closer

account and some alluring details about

the life of the greatest Arab and medieval

traveler.

From Tangier to 30 Years of Travels

Ibn Battuta was a North African Arab born

in Tangier, Morocco in 1304. His family

was a traditional Muslim family of judges.

As a youth, he learned Muslim law. In

1325, at the age of 21, he left his

hometown of Tangier to perform his Hajj.

Through his travels he also hoped to learn

more the practice of law across the Arab

world.

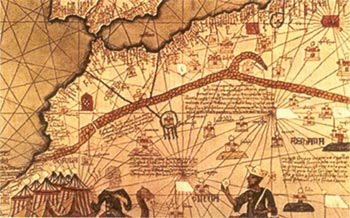

In the course of his first journey, Ibn

Battuta traveled through Algiers, Tunis,

Egypt, Palestine and Syria to Mecca. The

following is a passage from his own

records:

"My departure from Tangier, my birthplace,

took place ... with the object of making

the Pilgrimage to the Holy House (in

Mecca) and of visiting the tomb of the

Prophet (in Medina), God's richest

blessing and peace be on him. I set out

all by myself, having neither a

fellow-traveler in whose companionship I

might find cheer, nor a caravan whose

party I might join, but swayed by an

overmastering impulse within me and a

desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit

these illustrious sanctuaries. So I braced

my resolution to quit all my dear ones,

female and male, and forsook my home as

birds forsake their nests. My parents

being yet in the bonds of life, it weighed

sorely upon me to part from them, and both

they and I were afflicted with sorrow at

this separation."

In those years, traveling such great

distances and venturing into foreign

territories was risky.

Ibn Battuta was daring, or at least

determined, enough to start his journey

alone on a donkey. Along the way, perhaps

for safety, he became a member of a

caravan of traders, which grew as more and

more people joined in. By the time they

made it to Cairo, the caravan had several

thousand members and was still growing.

Ibn Battuta must have been very excited

about the progress of his trip. It was a

first-hand experience at learning about

his primary fascination - the larger world

of Islam, or Dar al-Islam. Thus he

was able to meet with learned fellow

Muslims and to gain increased experience

in religion and law.

Algiers and Libya

Upon reaching Algiers, the caravan spent

some time outside the city walls where

more pilgrims joined the group. As the

caravan reached Bijaya, Battuta’s health

deteriorated. He was determined to

continue however, and decided not to stay

behind in spite his poor health. In

reference to this incident he said: "If

God decrees my death, then my death shall

be on the road, with my face set towards

...[Mecca]."

When the caravan traveled through Libya,

Ibn Battuta found it appropriate to marry

the daughter of a Tunisian trader who was

traveling with the caravan for the Hajj.

Ibn Battuta married the girl in Tripoli,

but soon the marriage was broken because

of a quarrel between Ibn Battuta and his

new father-in-law. This didn’t seem to

bother Ibn Battuta, for he soon approached

another girl, a daughter of a pilgrim from

Fez. This time, the wedding was a lavish

celebration, which lasted a whole day.

Egypt and Syria

The caravan then headed toward Egypt. Ibn

Battuta was so immensely impressed with

Cairo – then, as now, the most opulent

Arabic city that he decided to spend

several months there. In any occasion,

there was still eight months before the

Hajj. In his own words, the city of Cairo

was “mother of cities ... mistress of

broad provinces and fruitful lands,

boundless in multitude of buildings,

peerless in beauty and splendor, the

meeting-place of comer and goer, the

stopping-place of feeble and strong. ...

She surges as the waves of the sea with

her throngs of folk and can scarce contain

them...”

Ibn Battuta stayed in Cairo for about one

month. Upon leaving the city he decided on

taking a less direct path to Mecca since

there were still several months before the

Hajj. He decided to visit Damascus – at

that time the second capital of the

Egyptian Mamluk Empire. This part of Ibn

Battuta’s journey was somewhat uneventful,

perhaps because he enjoyed relative safety

in this Mamluk governed terrain. Damascus

charmed Ibn Battuta with its atmosphere of

tolerance and supportiveness. "The

variety and expenditure of the religious

endowments at Damascus are beyond

computation,”

he wrote.

“There are endowments in aid of persons

who cannot undertake the pilgrimage to

Mecca, out of which are paid the expenses

of those who go in their stead. There are

other endowments for supplying wedding

outfits to girls whose families are unable

to provide them, and others for the

freeing of prisoners. There are endowments

for travelers, out of the revenues of

which they are given food, clothing, and

the expenses of conveyance to their

countries. Then there are endowments for

the improvement and paving of the streets,

because all the lanes in Damascus have

pavements on either side, on which the

foot

passengers walk, while those who ride use

the roadway in the centre"

In around 1326, Ibn Battuta at long last

performed his pilgrimage to Mecca. After

this, he realized that he was interested

more than ever in continuing to travel. He

had no special destination, and with his

only goal being to visit as many lands as

possible, he took care in choosing

different routes. He traveled across the

entire Middle East, from South in Ethipoia

to the north in Persia. "Then we

traveled to Baghdad, the Abode of Peace

and Capital of Islam. Here there are two

bridges like that at Hilla, on which the

people promenade night and day, both men

and women. The baths at Baghdad are

numerous and excellently constructed, most

of them being painted with pitch, which

has the appearance of black marble. This

pitch is brought from a spring between

Kufa and Basra, from which it flows

continually. It gathers at the sides of

the spring like clay and is shovelled up

and brought to Baghdad. Each establishment

has a number of private bathrooms, every

one of which has also a wash-basin in the

corner, with two taps supplying hot and

cold water. Every bather is given three

towels, one to wear round his waist when

he goes in, another to wear round his

waist when he comes out, and the third to

dry himself with."

Moving along further North, Ibn Battuta

took to exploring the Caspian and Black

Sea regions as well as the South of

Russia. His more interesting later travels

were to be further east in Asia. He

reached India, where he impressed the

ruling Mongol emperor with his knowledge

and tales. The emperor offered him a

position at his court, which Ibn Battuta

accepted. This gave him a chance to

explore the whole of India. Having gained

considerable experience during his travels

around the country, he was then appointed

as the Indian ambassador to China. This

occupation was destined to be the final

one for Battuta before he decided to

return home. Facing a long journey back,

he set out to his native lands. He reached

north-west Africa around 1351. He made a

short trip to Spain and then south to the

Sahara before finally coming to Fez,

Morocco in about 1353.

Back home and the Rihla

Back in Fez, the Sultan of Morocco, Abu

Inan (1348-1358 C.E), was so impressed to

hear Ibn Battuta’s account of his travels,

that he commanded him to remain in Fez and

store his tales in a book. Then, with the

help of an aspiring writer – Ibn Juzayy

al-Kalbi (1321-1356 C.E.) – Ibn Battuta

composed his popular “Rihla.” The Rihla,

or “The Travels” if translated, was

comprised of four separate volumes.

Perhaps, Ibn Juzayy has added a little

fiction from time to time for the purpose

of entertainment and easy communication,

but on the whole he is believed to have

strictly followed Ibn Battuta’s narrative.

Strangely enough, the Rihla did not become

popular until relatively recently, in the

19th century. This is when

increased contacts with Europe introduced

the book there and it was translated into

French, English, and other European

languages. The Europeans valued the

records of Ibn Battuta as an important

document of historical significance.

After finishing the Rihla, Ibn Battuta,

already a man of age, did not make any

long traveling through the deserts or

elsewhere. He took up a position as a

judge and continued to spread the wisdom

he had accumulated on his travels.

Although there are fewer records for the

last part of Ibn Battuta’s life, it is

known that he died in 1369 at the age of

sixty-five. Long years after this,

Ibn-Battuta remained the most traveled man

in the world.

Today, quite suitably, Ibn Battuta has

been honored in the field of exploration.

To commemorate his remarkable achievements

in voyaging, modern scientists have named

one of the Moon’s craters Ibn Battuta.

|