|

It

has often been suggested that Christianity

brought about the end of science. Whether

or not this is true, the Greeks’

inquisitiveness, for one, might have been

a threat for the forming faith.

Coincidence or not, as Christianity grew

in Europe, science declined and remained

suppressed for about one thousand years.

During this inactive period in Europe, the

vast Arab empire embraced science and its

learned men did much for the advancement

of world progress. It

has often been suggested that Christianity

brought about the end of science. Whether

or not this is true, the Greeks’

inquisitiveness, for one, might have been

a threat for the forming faith.

Coincidence or not, as Christianity grew

in Europe, science declined and remained

suppressed for about one thousand years.

During this inactive period in Europe, the

vast Arab empire embraced science and its

learned men did much for the advancement

of world progress.

One

field in which Arabic scholars excelled

was biology, which from the 3rd

until the 11th century was

essentially an Arab science. Chemistry

was another science in which the Arab

world took the lead. Most of the

chemists of the time were in fact

alchemists, busy in the pursuit of the

philosopher’s stone, which would

supposedly turn common metals into gold.

The philosopher’s stone was

never discovered. However, the efforts

spent in its search were not futile.

Numerous chemical substances were named

and characterized, some of which were

found to have medical value. Many drugs

now in use are of Arab origin, as are the

processes of distillation and sublimation.

One of the greatest

Arab contributors to science is Abu Ali

Al-Husayn ibn Abd Allah Ibn Sina, who

became one of the most influential

philosophers and physicians not only in

the Muslim world, but also on a global

level.

Ibn Sina’s early life

Born in 980 in Bukhara, Iran, Ibn Sina

(today also famous as Avicenna) was

tutored by his father in his forming

years. Ibn Sina’s father was a leader of

the Ismailiyah – a religious Islamic

society, which based its ideas on a type

of Neo-Platonism. Although young Ibn Sina

never followed his father’s convictions,

he benefited extensively from the fact

that many learned men often gathered to

converse and debate in his father’s house.

When he was only ten years old, Ibn Sina

had already memorized the Quran, many

Arabic poems and other literary works.

Ibn Sina’s early thirst for

knowledge soon took him to prominent

teachers of logic and metaphysics. By the

time he was eighteen years of age, Ibn

Sina found his tutors not needed any more

and went on to carry his studying by

himself. He acquired profound knowledge in

medicine, Islamic Law, and metaphysics.

Particularly helpful in his

intellectual development was his gaining

access to the rich royal library of the

Samanids- the first great native dynasty

that arose in Persia after the Arab

conquest. Ibn Sina was granted access to

the great library after he successfully

cured Prince Nooh Ibn Mansoor of the

Samanid dynasty of an illness in which all

the well-known physicians of the time had

given up hope.

By his early twenties, the young man had

become a popular and highly respected

physician. He was also given an

administrative post and soon wrote his

first book. Suddenly though, the whole

pattern of the young man’s life was about

to change. His father died, the Samanid

house was defeated and he began a period

of wandering and turmoil, which was to

mark the rest of his life with the

exception of a few unusual periods of

tranquility.

Destiny has plunged Ibn Sina into one of

the tumultuous periods of the history of

Persia. But being exceptionally gifted, he

managed to carry on with his intellectual

pursuits without being influenced by

outward disturbances.

Destiny has plunged Ibn Sina into one of

the tumultuous periods of the history of

Persia. But being exceptionally gifted, he

managed to carry on with his intellectual

pursuits without being influenced by

outward disturbances.

After wandering around

central Persia and failing to find the

necessary support and peace of mind to

continue with his studies, he then moved

to Hamadan, in west central Persia, where

the Shams ad-Dawlah was ruling. He cured

the ruler of colic and became court

physician and a vizier. At one point, a

mutiny of soldiers against him caused his

dismissal and imprisonment, but

subsequently the Shams ad-Dawlah, being

again attacked by the colic, summoned him

back with an apology and reinstated him.

The scholar’s life at this time was very

strenuous. During the day he was busy

fulfilling his duties as a physician and

administrator, while a great deal of the

night was passed in lecturing and

dictating notes for his books. Students

would regularly gather in his home and

would read parts of his great book, Al-Qanun

fi al-Tibb, which he had started

working on.

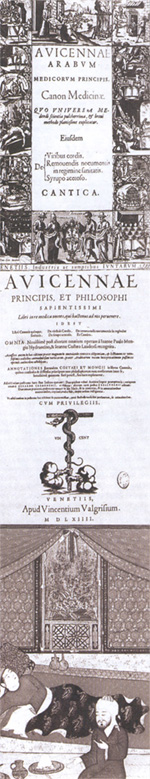

Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb

, also known as the Canon of Medicine,

is the most famous single book in the

history of medicine in both East and West.

It is a study encompassing and

systemathising the achievements of Greek

physicians as well as the entire medical

knowledge available from Muslim sources.

It is divided into five books. The first

contains a general expose on the human

body, sickness, health and general

treatment and therapeutics. The second

book contains the Pharmacology of herbs

and a section on experimentation in

medicine. The third book is all about the

subject of special pathology. The fourth

book follows with its famous treatise on

fevers and with a treatise on signs,

symptoms, diagnostics and prognostics,

minor surgery, tumors, wounds, fractures

and bites, as well as a chapter on

poisons. The fifth book contains the

pharmacopoeia, with a description of some

760 drugs.

In addition to bringing together the then

available knowledge, the book is rich with

the author's original findings. Ibn Sina’s

important contribution includes such

advances as recognition of the contagious

nature of phthisis and tuberculosis,

distribution of diseases by water and

soil, and interaction between psychology

and health. The first study to describe

meningitis and to make rich contributions

to anatomy, gynaecology and child health,

Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb became a

popular classic and was used at many

medical schools until as late as 1650.

In 1022 Shams ad-Dawlah died and Ibn Sina

found himself in a rather uncomforting

environment. This resulted in a period of

difficulty, which culminated into

imprisonment. Luckily, Ibn Sina found a

way to flee to Isfahan about 250 miles

south of Tehran. Accompanied by a small

entourage, Ibn Sina reached Isfahan and

decided to settle down. There he spent the

last 14 years of his life in relative

peace. He concluded his great work on his

al-Qanun as well as on Kitab al-Shifa',

his other monumental work.

Probably the largest work of its kind ever

written by one man, Kitab al-Shifa'

(The Book of Healing) embodies a

vast field of knowledge and medical

experience. Ibn Sina divided philosophy,

which he claimed to be the general name

for all knowledge, into two major parts.

One was speculative philosophy and the

other one was practical philosophy.

Speculative philosophy was divided into

four parts itself, which were

interestingly categorised. They were

physics - the inferior science,

mathematics – considered to be the middle

science, and metaphysics and theology -

the superior science. Practical philosophy

on the other hand was divided into ethics,

economics, and politics. These divisions

are of essential importance on account of

their influence on the arrangement of

sciences in the schools where the

philosophy of Ibn Sina preceded the

introduction of Aristotle’s works.

Kitab al-Shifa'

is also Ibn Sina’s most important work as

far as mathematics is concerned, as one of

the book’s four parts is solely dedicated

to the subject. Ibn Sina divided

mathematics into another four branches.

These he classified as geometry,

astronomy, arithmetic, and music, and he

then subdivided each of these topics even

further. Geometry he subdivided into

geodesy, static, kinematics, hydrostatics,

and optics. Astronomy he subdivided into

astronomical and geographical tables, and

the calendar. Arithmetic was made of the

components of algebra, and Indian addition

and subtraction. And, finally, music Ibn

Sina saw as a whole made up of the

subdivisions of the different musical

instruments.

During military campaigns Ibn Sina was

expected to accompany his patron, but he

still carried on with his writing. It was

on one of these military campaigns in 1037

that Ibn Sina fell ill. Despite his

attempts to cure himself, he could not

prevent the development of the sickness

and soon died.

Ibn Sina’s influence

Throughout his life, Ibn Sina's wrote

about 450 works of which only around 240

have survived. From his works in existence

today, 150 are on philosophy while 40 are

devoted to medicine, the two fields in

which he contributed most. He also wrote

on psychology, geology, mathematics,

astronomy, and logic.

All of his books and treatises were

written in Arabic, with the exception of

two works, which were written in Farsi –

Ibn Sina’s native language. The first one

is the `Daneshnameh-e-Alai' (Encylopedia

of Philosophical Sciences), the second - a

small treatise on the pulse, which later

became quite famous.

In the 12th century Ibn Sina's Kitab al-Shifa'

was translated partially into Latin. The

complete al-Qanun also appeared in Europe

around this time. These translations and

others spread his thought far and wide. In

medicine al-Qanun became the undisputed

medical authority for several centuries,

granting the scholar a place of honor

equaled only by the early Greek physicians

Hippocrates and Galen. The fame of the

book was such that its author became known

as the "Prince of Physicians" in the West.

Also known as al-Sheikh al-Rais (Leader

among the wise men), a title given to him

by his students, Ibn Sina contributed

significantly to the field of astronomy.

He made astronomical observations while at

Isfahan and later - at Hamadan. These

studies produced a number of deductions,

which proved to be true centuries later.

For example, he observed Venus as a spot

against the surface of the Sun and

correctly deduced that Venus must be

closer to the Earth than the Sun. He also

invented an instrument for observing the

coordinates of a star.

In physics, his contribution comprised the

study of different forms of energy - heat,

light and mechanical energy, as well as

such concepts as force, vacuum and

infinity. He made the important

observation that if the perception of

light is due to the emission of some sort

of particles by the luminous source, the

speed of light must be finite. He

propounded an interconnection between time

and motion, and also made investigations

on specific gravity and used an air

thermometer.

He also contributed to the field of music and is the reported

author of Persian quatrains and short

poems:

"Up from Earth's Centre through the

Seventh Gate I rose, and on the Throne of

Saturn sate, And many a knot unravelled by

the Road, But not the Master-knot of Human

Fate."

His treatise on minerals was one of the

main sources of geology of the Christian

encyclopaedists of the thirteenth century.

Ibn Sina's major contributions are in

philosophy. Although he found Aristotle’s

teachings too hard to incorporate into

practical knowledge, he wrote numerous

treaties discussing his teachings. Ibn

Sina’s philosophy synthesises Aristotelian

tradition, Neoplatonic influences and

Muslim theology. In Latin translations,

his works influenced many Western

philosophers and scholars, most notably

Thomas Aquinas. |