|

The

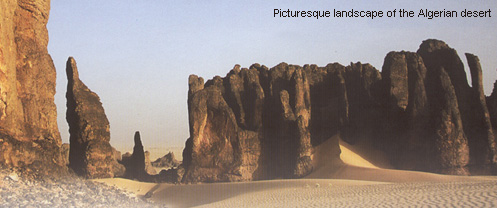

year was 1974. It had been a long journey

and we were dishevelled, exhausted and

hungry. There were three bottles of water

left, but I would have cheerfully handed

over my life savings for an English cup of

tea. We had driven in a tiny Citroen Deux

Chevaux from London to deep in the

Algerian Sahara traversing France, Spain

and Morocco. Now, it seemed we were on a

road to nowhere with a vast expanse of

desert interspersed with giant rocks as

far as the eye could see.

The

year was 1974. It had been a long journey

and we were dishevelled, exhausted and

hungry. There were three bottles of water

left, but I would have cheerfully handed

over my life savings for an English cup of

tea. We had driven in a tiny Citroen Deux

Chevaux from London to deep in the

Algerian Sahara traversing France, Spain

and Morocco. Now, it seemed we were on a

road to nowhere with a vast expanse of

desert interspersed with giant rocks as

far as the eye could see.

Darkness would fall

shortly and there was no sign of the

Mízab towns as our guidebook had

indicated. With the reckless

over-confidence of youth, it didnít

occur to us that we might be lost and

all that could mean. Instead, we

listened to the strains of Sawah

- a recording by the Egyptian singing

icon Abdul Halim Hafez - its grand

orchestral reverberating off the

boulders and adding to the mystique of a

never to be forgotten moment.

Mízabites

Suddenly, without warning, the tarmac road

ended and below us like a mirage stretched

a lush valley of palm groves and gardens

towered over by the minarets of the

Mízabís five towns - Ghardaia, Beni

Isguene, Bou Nouara, Melika and Al-Ateuf,

flanking a winding wadi.

We headed for the

largest town Ghardaia and in retrospect

Iím not sure whether we were more

surprised to see them or the Mízabites us.

Strangers were an uncommon sight in those

days, especially the fair-haired variety

in Western garb.

We passed though the

gate of the walled town and arrived in its

large square at prayer time when the

sounds of the muezzin echoed over the city

inviting the faithful to pray. In awe at

their piety, we watched as hundreds of

bearded men dressed in baggy Turkish-type

black trousers flooded out of their homes

and hole-in-the-wall shops in response to

the call. Others turned up on donkeys used

to trotting down the stone steps of narrow

alleyways. There wasnít a car to be seen.

Suspicious of

foreigners, a French-speaking shopkeeper

didnít encourage us to stay in the

Mízabite town after dark and so we rented

one of his summerhouses, a villa set in an

oasis outside the walls.

The nearby

town of Beni Isguene, considered holy, was

completely off-limits to non-Mízabites.

Few foreigners have been allowed a tour of

that town where music, alcohol and smoking

are forbidden. Those who have managed to

visit describe scrupulously clean streets

devoid of litter and stylish homes.

After a delicious

repast of cous-cous, I spent the night on

the villaís roof marveling at the myriad

stars, which shone brighter than anywhere

I had known before and listening to the

silence, the kind of silence that only the

desert can produce.

The Mízabites are a

secretive people and their origins are

difficult to decipher, although it is

thought that they descended from Berber

followers of Abdullah Ibn Ibad Al-Tamimi

of Basra. When their mountain stronghold

of Tiaret was destroyed by the Fatimid

Empire in AD 909, it is believed the

Ibadis fled to the Sahara for safety.

Despite the

inhospitable terrain, the Mízabites became

wealthy from the fruits of their date

palms, watered from thousands of wells

bored deep into the earth and an ingenious

irrigation system. Besides the more than

160,000 palm groves, these wells provide

water for the 100,000 inhabitants of the

Mízab and their herds.

Believers in the evil

eye, Mízabites construct their homes with

modest facades. However, their interiors

are elaborately decorated and richly

furnished. All have flat roofs where the

shy Mízabite women spend their leisure

time and they are built so close together

that a woman can hop from roof to roof so

as to visit family and friends.

Traditionally their

husbands do all the shopping or, else, the

family servant, while women are rarely

seen on the streets. Young women often

never leave their homes except on the day

they marry but on the rare occasions older

women venture forth, they are heavily

veiled, displaying only one eye.

Mízabite men are famed

throughout Algeria as accomplished

businessmen and traders and often spend

long periods away from their homeland, but

always with the thought of making enough

money to retire to the peace and

tranquillity of their beloved desert

valley.

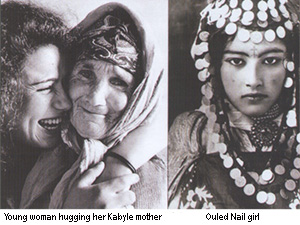

Ouled-Nail

Earlier in our journey through Algeria -

one of the most beautiful and diverse

countries in the world - we had passed the

large black tents of the Ouled-Nail

dotting a mountain range near Djelfa. Now

we were headed for Biskra, a desert

oasis town forever associated with Ouled-Nail

dancers.

At the other end of

the spectrum from the puritanical

attitudes of the Mízabites, the daughters

of the Ouled-Nail were trained in the art

of dance and song from childhood so as to

earn a living entertaining the inhabitants

of desert towns. The profession is

hereditary, and the girls would return

from their years away from the tents

adorned with necklaces of gold coins

without a blemish on their name within

their own society. There they would put

their dancing days behind them, marry and

set their sights on being good tent-wives.

Biskra was a modern

town compared to those of the Mízab with

several relatively good hotels. As luck

would have it, we arrived in the midst of

a tribal festival and soon discovered

there was no room at the inn. Instead, we

were pointed in the direction of the

townís Tourism Office, which arranged for

us a nightís accommodation in the home of

a local family.

We accepted the offer

sight unseen and found ourselves sleeping

on straw pallets on the floor along with

the occasional wandering chicken. It

seemed surreal that perched on an oak

chest of drawers was a battery-operated

record player, which boasted a single

record - Alain Barriereís Ma Vie, a

particular favourite of mine at that time.

There was no bathroom

in the mud-built house, and so the

following morning we strolled to the local

hammam or Turkish-style bath before going

in search of the Ouled-Nail dancers who

proved to be elusive.

Instead, we reached

the town square where burnoose-clad,

rifle-touting tribesmen raced on

horseback, snake charmers bedazzled the

crowd and folkloric troupes put on

traditional shows of song and dance. The

air was filled with the aroma of merguez,

a spicy red sausage, which we bought from

a stallholder and devoured with relish for

breakfast.

We spent the next

three days lounging by the pool of one of

Biskraís best hotels and basked in the

luxury of rooms with en suite baths and

the ability to order cafi au lait or ice

cream from room service. We had planned to

continue our journey to Tamanrasset, home

of Algeriaís most famous tribe - the

Toureg, otherwise known as Ďthe blue mení

but our Citroen refused to go another

mile. Once it was repaired, we thought it

prudent to return to Algiers, rather than

continuing southwards.

Tuareg (Les hommes bleus)

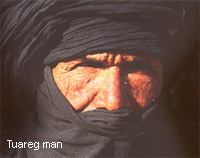

The Tuareg were once

ferocious warriors responsible for the

deaths of many an intrepid explorer and

feared by everyone who dared to cross

their territory. They were lords of the

traditional salt, slave and gold caravan

routes with a feudalistic culture and

their own written language.

Called the Blue Men due to

the indigo dyes used to colour their

robes, the Tuareg man are veiled and while

not engaged in combat once spent their

days performing elaborate tea rituals and

gathering their strength for the next

inevitable conflict.

They fought bravely and

honourably preferring to use swords,

knives and shields rather than more modern

weapons and almost always overwhelmed

their foes with their superior courage and

skills.

|

|

|

Tuareg guides |

Photo courtesy of Peter Klaunzer |

In the late 1800s, the French occupiers

of Algeria decided to build a railway

through the Sahara and were beaten back

by Tuareg warriors. Such was their

ferocity that eventually the plan was

dropped.

Archaeologist Count Byron

Khun de Prorok talks about the Tuareg in

his book Mysterious Sahara. This

1920s work describes the Tuareg as ďthe

giant white race of the SaharaĒ. Prorak

came face to face with 5,000 Tuareg,

wielding swords and was lucky not to

suffer the same fate as many of his

contemporaries, brutally killed on sight.

The Tuareg is a matriarchal

society where the women go unveiled and do

most of the work. Prorok wanted to find

the tomb of their queen Tin Hinan in the

belief that it would yield up clues to the

tribesí origin.

He finally discovered the

remains of the queen herself along with

ancient Roman coins and other

Mediterranean artifacts, as well as gold

necklaces and bracelets, all of which he

looted before the Tuareg could discover

just whose tomb it was.

Tragically, the advent of

the 20th century proved the

undoing of the Tuareg. Their legendary

horsemanship has now been relegated to a

tourist attraction while their lands are

parched from drought and stricken by

poverty. Yet they still manage to retain

their noble aspect and regal bearing.

|

M'zabites performing traditional

tribal dance

Photos courtesy of Taha Baali,

www.mzab.free.fr |

Kabyles

On our way back to the

capital, we made a detour so as to pass

through Tizi Ouzou, the principal Berber

town, then peaceful and picturesque.

Kabyle women wearing brightly colored

dresses smiled and waved at us before we

stopped at a roadside cafi for freshly

squeezed melon juice. The owner wanted to

give us a souvenir of our visit and pulled

out a picture of his baby son Laghdar. I

was supremely touched and still cherish

it.

The Berbers, thought to be the indigenous

people of Algeria fought the Romans, the

Arabs, the Turks and the French, who spent

almost 30 years trying to take over their

mountain strongholds. Today, they are

struggling to retain their own identity,

culture and language in a country beset by

political problems.

I know that the clock canít

be turned back, but from a selfish point

of view, I long for the day when itís safe

to retrace my steps. Who knows! Perhaps I

will track down Laghdar, now a portly

pater familias; say hello to the

barbery apes of the Chiffa Gorge; walk in

the forests of Seraidi, a delightful

mountain-top village overlooking Annaba;

hunt for rose du sables (quartz rocks) in

the Sahara or immerse myself in the hot

springs at Guelma. In the meantime, like

the Tuareg, I can but dream of the past

and trust in a better future for the

long-suffering Algerian people.

|