|

The

Suez Canal, as it is called today, links the

Mediterranean Sea with the Red Sea by a waterway. It is

perhaps one of the oldest enterprises of the world, ever

considered by man. The Pharaohs of the ancient times had

recognized the advantages of such waterway passing

through Egypt. They believed the linking of the two seas

would ensure a safe, speedy and economical means of

transport for the vessels sailing through it. This

waterway would also be of great commercial importance to

Egypt.

Geographically,

Egypt formed the natural gateway between the East and

the West. The wealth and the produce of nations passed

through her intercontinental trade routes. Since ancient

times, merchants of the world had passed through Egypt

selling their wares and exchanging goods from far-flung

countries of the world. Traders from Europe constantly

traveled to Egypt by sea. The possessor of Egypt also

ruled the mart of the world. It was therefore natural

that the empires of the world from the earliest times

sought the conquest of Egypt through land and by sea for

its strategic location and unique commercial position in

the world.

To the east of

Egypt was a narrow neck of land-the Isthmus of

Suez-joining Africa with Asia. It was also noticed that

the waters of the Red Sea flowed close to the

Mediterranean Sea. Not so far to the West was the River

Nile, running in a parallel course to the sea with one

of its channels crossing the edge of the Isthmus. As a

result, the acute minds of the world 4000 years ago

thought about the possibility of providing the Nile with

an additional artificial mouth, linking it to the Red

Sea connected to the Mediterranean through its delta

channel.

The earliest

Egyptian canal builders were mainly concerned in

expanding the highly profitable trade carried through

the land routes, providing the merchants with a passage

through shipping vessels to carry their trade to the

great interior cities along the Nile River, enriching

the country with gold, ivory and spices brought from the

Arabian Gulf and the East African coast.

The details of

the construction of the first navigable canal, linking

the Nile with the Red Sea have been lost in antiquity.

Tradition records that it was Sesostris, a Pharaoh of

the Twelfth Dynasty, who first set his hand to the work.

During the next thousand years, the canal was available

for commerce and it was known then as the Canal of the

Pharaohs. Political upheavals in Egypt caused the

maintenance of the canal to be abandoned in the

beginning of the 7th century BC.

Later, the

famous Pharaoh Necho (612 BC) took upon the task of

cutting the canal employing 120,000 slaves on the labor.

But he was persuaded to dump the project midway by his

court astrologers, who warned that he was preparing the

way for an invader from foreign lands to occupy Egypt.

It is believed that this prophecy came true after Darius

(521 BC) conquered Egypt after the death of Cambyses II.

He restored and enlarged the canal. A record of his

achievement discovered recently states: “I ordered

the canal to be dug up from the River called Pirava (the

Nile), which follows in Egypt to the sea that comes out

of Persia (The Red Sea).” Subsequently Darius for

reasons unknown destroyed the last part of the canal,

which was later restored by his successor Xerxes.

Under the

Ptolemaic Dynasty the Canal of the Pharaohs was enlarged

ending in a place called Arsinoe, near the modern Suez

Port. Ptolemy Philadelphius (286 BC) proposed cutting a

canal directly through the Isthmus, joining the two seas

together. He was made to abandon his project for it was

believed that the level of the Red Sea was higher than

that of the Mediterranean, and this in turn would cause

the flooding of the entire country if the canal was

built-a belief that persisted until the beginning of the

nineteenth century. If it had not been for this error in

calculating the level of the two seas, a canal would

have come into being two thousand years ago!

During the Roman

occupation of Egypt, the Canal of the Pharaohs was

renamed as the River of Trajan. The Emperor Trajan who

ruled Egypt from 98 CE to 117 CE devoted much of his

attention in construction and improvement of harbors. He

got the old canal cleaned and gave it a better water

supply by uniting it with the main stream of Nile near

Cairo. As it was constructed then, the canal took the

shape of an arc and remained navigable until some time

in the 3rd century CE. By the time Emperor

Constantine (285 CE) took over the reign of the Roman

Empire, the canal had been again put out of commission.

With the Arab

conquest of Egypt in the 7th century CE, the

Nile-Red Sea Canal entered the last phase of its

history. After taking permission of Caliph Umar, Amr ibn

al-Aas, the Governor of Egypt had the canal reopened in

the winter of 641-642 CE. The canal rendered useful

service to the people of Egypt until the end of the 8th

century under the name “Canal of the Commander of the

Faithful.” During his rule as Governor of Egypt, it

was proposed to Amr ibn al-Aas cutting a canal from Lake

Tismah in the middle of the Isthmus to the Mediterranean

Sea. But the project was dropped due to military

reasons. The canal was closed in 776 CE by Caliph Abu

Jafar al-Mansour to check the revolt against his empire

from the Holy Cities of Makkah and Madinah.

From this time

onwards, the commerce between Egypt and the rest of the

world steadily declined. Turkey had gained complete

mastery over the shipping in the Mediterranean Sea. The

traffic of European merchants sailing to Middle Eastern

countries in the Mediterranean had almost come to a

complete halt. During this period the Arab traders had

introduced spices to Europe. Realizing they controlled

commodities that were in great demand in Europe, the

Arab traders kept their sources of supply a secret and

made up fantastic tales about the dangers involved in

obtaining the spices.

In bits and

pieces, the Europeans learnt about the Land of India in

the East, famous for its riches and spices. A new route

from the sea had to be discovered in the face of the

Turkish barrier. The vast wealth of the Venetians

arising from acting as middlemen in the spice trade with

India had earned them the envy of all European nations.

Portuguese sailors, encouraged by Prince Henry, the

Navigator, had explored most of the west coast of Africa

in the early 15th century. Christopher

Columbus set sail from Spain in 1492 and headed west

hoping to hit the Indian coast where the precious

commodities could be found. Another famous voyager,

Vasco da Gama, traveled from Portugal and succeeded in

rounding the Cape of Good Hope and reached India in May

1498. He brought back a letter from Zamorin to the King

of Portugal that the ruler of Calicut was willing to

barter spices for gold, silver and scarlet cloth.

At last, the sea

route to India had been discovered, which gave the

Europeans a complete monopoly of the spice trade to

India and the countries of the Far East for the next

four hundred years. The people of Venice took hard the

loss of their spice trade to other European powers of

those times. As early as 1504, they had thought about a

plan of suggesting to the Sultan of Egypt the

possibility of cutting a canal through Egypt, joining

sea to sea.

At the end of

the 16th century, the then Turkish Pasha of

Egypt, Al-Hajj Ali suggested to the Sultan of Turkey the

reopening of the Nile-Red Sea Canal with access to the

Mediterranean, across the Isthmus, which would

facilitate the transport of materials across the

waterway by the Turkish fleet. The Sultan was greatly

fascinated by this project but was deterred in

sanctioning it owing to the difficulties in carrying it

out, and the heavy cost involved. By then the French had

taken a keen interest in getting a canal cut from Suez

to Cairo as it would lessen the cost of goods imported

from India through ships and weaken the hold of

Spaniards over the Mediterranean Sea.

However, the

political difficulties, apart from the practical ones,

in conquering Egypt appeared formidable. Leibinitz, a

German philosopher urged Louis XIV to seize Egypt and

secure for the nation of France the riches of eastern

traffic. Jacques Savary, a 17th century

French trader in his book “The Complete Merchant”

advised the French Government about the advantages that

would accrue to France by cutting a canal through the

Isthmus. He writes: “Britain would loose her position

as the mistress of the seas and her commerce through the

Cape of Good Hope destroyed leaving France in control of

the safest and speediest trade route to India and

Far-East.” The plan of constructing such a canal was

debated endlessly by the merchants of France.

In the meantime,

Turkey continued to control Egypt and was content in

letting the goods shipped from India to Suez to be

carried by camels to Cairo, then conveyed by canal to

Alexandria and finally transshipped to Europe. It was

also evident to the Government of France that the power

of Turkey over Egypt was weakening. For the moment,

France satisfied itself in negotiating passage rights

for her merchants with the Beys, who ruled Egypt at that

time.

On the other

hand, the British traders were more aware of the designs

of France, long before the British Government took

notice of it. George Baldwin of the British Levant

Company warned England: “France in possession of

Egypt would possess the master-key to all the trading

stations of the earth. Enlightened in navigation and

commerce, she might make it the emporium of the

world-transporting her force in any manner and at any

time; England would hold her possessions in India at the

mercy of France.” Colonel James Capper of the East

India Company in his book in 1785, warned England in

depending on a single trade route, which at some point

in time may be superseded by the discovery of a better

one.

So matters stood

at the beginning of the last decade of the 18th

century. War broke out between England and France in

1793. Four years later, Napoleon Bonaparte felt that in

order to destroy England, it was necessary for him to

possess Egypt. Soon, Napoleon landed his forces in

Alexandria and occupied Egypt, a move that took England

completely by surprise. He lost no time in undertaking

the task of cutting a canal through the Isthmus, which

was the primary object of his expedition.

For this

purpose, he hired the services of a number of engineers

and scientists. A survey was instituted and carried out,

headed by the famous engineer J.M Lepere. Lepere

estimated that it would cost France 1,500,000 pounds and

would occupy ten thousand workmen four years to do the

job. But, the fortunes of war soon turned against

Napoleon and the peace of Amiens in 1802 ended the

French territorial ambitions in Egypt. But France never

lost interest in Egypt or the Suez Canal Project.

By the beginning

of the 19th century, Muhammad Ali Pasha

managed to seize power in Egypt and proclaimed himself

Viceroy. He introduced sweeping administrative and

military reforms. Most of his efforts were directed in

improving Egypt’s infrastructure such as canals and

roadways. In 1819, a new canal known as the Mahmudiya

Canal (named after the Sultan of Turkey) was dug. It

linked Alexandria with Nile. Muhammad Ali Pasha died in

1849 without making his dream of constructing a canal,

joining the two seas a reality.

It was finally

left to the genius of Ferdinand de Lesseps, a former

attaché of the French Consul in Alexandria to bring

about the successful completion of the canal in the year

1869. Lesseps had earned for himself the reputation of a

humanist with a world outlook. His intentions behind

constructing the canal had nothing to do with the power

politics in his time. He desired to give the nations of

the world a speedy way of transit that would that would

unite the countries of the West with those of the East,

and enrich them in trade.

Born at

Versailles in 1805, Lesseps came from a family of

diplomats. Earlier his father had been posted as the

French Consul in Egypt and has assisted Muhammad Ali

Pasha in his rise to power. After holding various

diplomatic posts overseas, Lesseps returned for a second

time to Egypt. While waiting to land from his vessel at

Alexandria, he came across a copy of Lepere’s memorandum

on the proposed Suez Canal. His imagination was fired by

this grand concept, for he had never forgotten his

youthful vision of a cutting a canal through Egypt that

would link the two seas on either side of the Isthmus.

After landing in

Egypt, Lesseps struck a lasting friendship with Muhammad

Said Pasha, the youngest son of Muhammad Ali. Lesseps

devoted himself to the task of studying every aspect of

Lepere’s proposed project of the Suez Canal. Two years

later, Abbas Pasha who was the Viceroy of Egypt, died

and his friend Muhammad Said replaced him as the ruler

of Egypt. Lesseps was now ready with all the details and

the principal facts of the Suez Project. At the earliest

opportunity, he explained to Muhammad Said his vision of

constructing the Suez Canal without entering into

details, dwelling mainly on the main points written in a

memorandum, which he had carried with him.

Muhammad Said

was a man of considerable intelligence, and raised few

objections that were immediately explained to him by

Lesseps. In the end he was convinced. He said to the

Frenchman: “I accept your plan; we will concern

ourselves as to means of carrying it out. You may regard

the matter as settled, and place your trust in me”.

Lesseps had won the Concession from the Prince in a day,

which was drawn on broad lines in November 1854. By it,

Lesseps was authorized to form an international company

under his own direction, the “Compagnie Universelle

du Canal Maritime de Suez.” The Concession would be

in force for 99 years from the date of opening of the

Canal and had to be ratified by the Sultan of Turkey.

The news of the

Concession came as a bombshell when a public

announcement was made on the making of the Suez Canal.

France and Austria were naturally pleased, but England

expressed her misgivings through the British Consul

General in Egypt. Her Majesty’s Government regarded this

scheme with disfavor. Lesseps was quick to realize that

he had to contend with the full force of the British

opposition to his venture. He therefore, hastened to

Constantinople to secure the support of Sultan of Turkey

before the opposition took on a concrete form.

On reaching

Constantinople, Lesseps found to his dismay that all his

efforts in seeking the Sultan�s ratification for his

project were being thwarted by Lord Redcliffe, the

British Ambassador who was using his influence with the

Sultan and the Grand Vizier to withhold their assent. He

knew he had to take England into his confidence if he

wanted his project to be successful. Lesseps therefore,

decided to travel to London. Arriving in London in June

1855, he first called upon Lord Palmerston, the Prime

Minister of England to apprise him about the project.

The Prime Minister made it clear that he was opposed to

the venture, as it would harm British maritime and

commercial interests, and would give France an advantage

over the sea routes.

Lesseps decided

to talk directly to the British merchants and ship

owners having business with India of the enormous

financial advantages of his project. The British traders

were quick to realize the feasibility of his project.

Pleased at the receptive audience, Lesseps decided to

push ahead on his advantage by setting up an

international committee of the best engineering brains

in Europe to convince his opponents on the advantages of

the Suez Canal project. The committee submitted its

report in January 1856. The report stated; “Our

investigation has revealed to us that the execution of

the work on the Canal is easy and its success assured.”

Lesseps decided

to sell the shares of his company in the open market.

France purchased half of its shares, and some of it sold

to others in European countries. Armed with the initial

capital, Lesseps decided to push ahead with the digging

of the Canal without waiting for approval from Turkey.

Alarmed at this move, the British Government tried every

kind of intimidation to make him abandon his work. In

desperation, Lesseps appealed to Napoleon III, the

Emperor of France for help. The Emperor assured him all

financial assistance and protection.

Operations were

resumed, and by October 18th 1862, the waters

of the Mediterranean entered Lake Tismah, an achievement

that impressed even the British observers. The canal had

been cut through a waterless region of sandy waste and

it provided drinking water to thousands of workmen

engaged in the task of building the canal.

Unfortunately, the British continued to oppose the

project along with the Sultan of Turkey. On January 18th

1863, Lesseps’ friend and patron Muhammad Said died and

his successor Ismail ranged himself boldly on the side

of the enterprise. Faced with opposition, Lesseps again

appealed to the Emperor of France to arbitrate on the

behalf of the company. After complicated negotiations, a

deal was reached that was acceptable to all parties.

On March 16th

1866, the Sultan of Turkey gave his sanction to continue

work on the Suez Canal. Released from the crushing

weight of governmental opposition the construction of

the canal proceeded swiftly. Machinery and dredgers were

brought to replace the heavy labor loss. The excavations

continued southward from Lake Tismah and northward from

Suez until the waters of the Mediterranean and the Red

Sea were united in Bitter Lakes in the summer of 1869.

The Suez Canal that was built was about 104 miles long,

with minimum bottom width of 150 feet, and has a depth

of 33 ft.

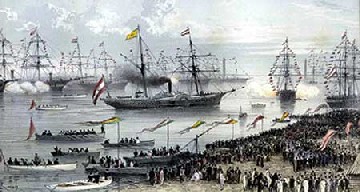

The official opening of the Suez Canal took place on

November 17th 1869 attended by many royal

dignitaries and distinguished persons. Praise for its

achievement poured from different parts of the world.

The Suez Canal was now seen as universal in its

benefits. A procession of sixty-seven vessels, headed by

the Imperial yacht Aigle with Empress Eugene and

De Lesseps on board filed into the Canal at Port Said

and, after nights at anchor in Lake Tismah and the

Bitter Lakes, the Suez was reached in the morning of

November 20th. Thus, the great hopes, which

were entertained by De Lesseps, of this mighty

undertaking were realized. His patience, perseverance

and unwavering faith in this project had paid off. He

had successfully surmounted all difficulties and crises

that were thrown in his way. At last, the centuries old

dream of joining the two seas together had become a

reality. |