|

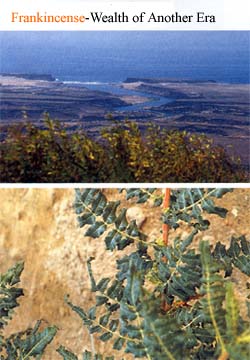

Frankincense, myrrh and gold are known throughout the

world as the gifts that kings from the East made to the

baby Jesus. Of these three “commodities”, frankincense,

also called oblibanum, was by far the most precious and

expensive. The incense consisted of translucent drops of

crystallized resin from the frankincense tree, which

later became known scientifically as Boswellia sacra.

This shrubby tree grew in the southeast of the Arabian

Peninsula - in the Dhofar and Hadramauth regions. Other

frankincense existed (and still exists) also: in India

from another Boswellia species, Boswellia serrata;

and from Somalia, which had Boswellia frereana as

well as Boswellia sacra. But the best

frankincense was and is produced by the trees that grow

in the Dhofar region and even in one particular area of

the Dhofar - Hasik, 10 km inland from the coast in the

northeast and reached by crossing the pass of Bab-Harkek.

When

you visit Salalah nowadays, the frankincense trees are

not much in evidence - although one specimen flourishes

in the garden of the Holiday Inn Hotel. The wild growing

trees are hidden in the gullies and valleys of the arid

parts of the Qara and Samhan mountains, just outside the

reach of the wet monsoon rains.

Why

was frankincense so famous and valuable?

The

incense has a multitude of medicinal uses and has always

been used in religious ceremonies as well as in royal

households. It is produced by a small tree that looks

insignificant. Its local name is mughur, (mogar, megerot)

or sajerat alluban. It can have many stems, giving it a

bush like appearance. The tree can reach a height of 5

meters but is often much more stunted. The stems are

covered with a reddish-brown bark that loosens into

papery peeling strips. The leaves are feathery, with

small leaflets with crinkly edges. The flowers are

crowded at the end of branches, on small spikes. They

have five white petals and an orange center that turns

black later on. The fruit is a reddish-brown capsule

with one seed in each of its 3-5 compartments. All parts

of the tree contain amounts of resin, an oleo-gum-resin

that is composed of 60-70% alcohol soluble resin and

5-9% volatile oils, with the remainder being

water-soluble resins. It exudes from cuts in the bark

that are either man-made or occur naturally. The opaque

milky substance, called luban or shahaz, dries into

small tear-shaped lumps that crystallize into a clear

silvery solid substance. The essential oil component

contains more than 200 individual natural chemicals that

give the incense its very complex bouquet.

Wild-harvested frankincense is a unique material.

Historically, two different tribes have been involved in

the frankincense harvest: the Jabali’s who live in the

grass lands of the mountains surrounding the Salalah

coastal plain, and the Bedouins from the desert regions

north of the mountains. The Jabali’s are a

cattle-raising community who guarded the vegetation-rich

lower hills from over-grazing and prevented

environmental degradation for thousands of years. The

Bedouins are nomadic and still maintain their old

traditions. They used frankincense when they performed

their morning prayers at the entrances of their houses

and animal-shelters to protect the inhabitants from the

djinn.

The

precious resin is harvested during two seasons: the

spring harvest that lasts from March till May (winter

gum or ‘shahaz estebi’) and the fall harvest that is

from late September till October. The latter season,

called the “kharif”, produces the best resin (shahaz

kharfi), which is white in colour. Of this, the best

resin is produced by the high dry mountains of the Nejd

and is called ‘shahaz negdi’. Each tree belongs to

specific families and the guardianship of these trees is

passed on from generation to generation.

To

harvest the resin, the trees are scored by a

wooden-handled tool with a sharp metal blade, the

mengaff. The resin that flows from the wounds in the

tree bark is gathered in two-week intervals. Only the

material that dries on the tree is collected in the

first instance, although some of the resin flows to the

base of the tree - this is harvested all at the same

time at the end of the season.

The

collected resin is allowed to mature for three months

and is stored on the floor of dry caves.

The

trade and uses of frankincense have been mentioned in

ancient documents. Ptolemy mentioned the

frankincense-producing region as “the mountains of Ophir”,

now thought to be synonymous with the mountains of

Saphar or Dhofar. The Syriac Book of Medicine mentions

remedies, in which frankincense is used. Similar texts

are found in the texts of medieval Muslim practitioners

and in ancient Indian and Chinese medical documents.

During the height of the trade, the harvesting was often

done by slaves and banished criminals. The gum

collectors suffered many hardships, including the many

endemic diseases that exist in the region. The trade was

controlled by whatever king ruled the area at any given

time. Manual de Almeida, a 17th century traveling

Portuguese Jesuit was told that the king of Dhofar and

Qidr owned all the frankincense in the world. De Almeida

was also the first person to describe correctly the

habitat of the frankincense tree: not the verdant lower

seaside hills, but the arid wadis and hills north of the

rainfall area.

The

frankincense trade was the main source of income for the

Dhofar region for almost 5000 years. It was transported

by sea via ports such as Khor Rori with its protective

fort of Samharan and Ganna (with Hisn al Gorab as its

protection) in the Dhofar, and Mukha in what is now

Yemen. From there, it went to India and other parts of

Arabia. However, travel through the Red Sea was fraught

with danger, both from coral reefs and pirates.

Therefore, a land route was developed, first traveled

with donkeys and mules. These, however, needed daily

watering and therefore had to travel complicated zigzag

routes via all the known wells in the desert. Around the

11th century BC camels started to be used as the animal

of transport. These hardy animals could travel without

water for several days, even weeks on end, which made it

possible to travel in straight lines. From a point just

north of the Nejd, the routes ran parallel to the coast

westward and northward. Just before the decline in the

frankincense trade 3000 tons of frankincense were

shipped by camel caravans each year from south Arabia to

Greece, Rome and the Mediterranean world.

Everywhere along the land routes people profited from

this lucrative trade: cities levied taxes at the gates

and at the temples; guards, porters, and servants had to

be bribed; tradesmen sold accommodation, food, animal

fodder and water at the caravanserais; robbers set up

check-points and demanded high bribes for safe passage.

The wealth produced by the frankincense trade supported

many settlements and made them into rich city-states

that could construct sophisticated dams and irrigation

systems, such as at Marib in Yemen. Not only

frankincense was transported via the Incense Route,

but also silks and spices that Omani seafarers had

imported from India and China. This led the Romans to

believe that the kingdoms of southern Arabia produced

these goods. Logically the Romans desired to conquer

these regions that produced such valuable commodities

and sent Aelius Gallus to do so. He never made it

because lack of water kept him in Yemen. It was again

the lack of water, as well as the shifting sands, that

defeated the British explorer Bertrand Thomas in the

1930’s when he tried to explore the ancient frankincense

trail. In the 1980’s NASA’s satellites in space took

pictures that showed faint shadows of a network of roads

under the dunes that in these parts reached heights of

200 to 600 feet. Hundred-meter wide hoof-trodden paths

lay hidden under tons of sand and converged on a point

in the desert that could be the center of the lost

civilization of Ad, the "Atlantis of the sands". In 1990

a scouting expedition that included NASA’s Charles

Elachi and Ronald Blom as well as British explorer

Ranulph Fiennes, Los Angeles attorney George Hedges and

a crew of archaeologists, geologists and documentary

filmmakers looked for geological evidence of a trail to

the once-thriving city of Ubar, the main frankincense

shipping center of Ad. The Ad civilization lasted from

3000 BC to the 2nd century AD and ended when the demand

for frankincense dropped due to worldwide changes in

politics, economics, climate and customs. The explorers

found 900 pottery shards and flint pieces from the Ad

era on this trade route. Excavations had been planned

for 1991 but were postponed due to the first Gulf War.

Even

though the frankincense trade had diminished in the 3rd

century AD, there was still demand for the commodity and

trade continued at a lower level well into the Middle

Ages. Evidence of the use of frankincense was found in

Egypt as charred remains of burnt Boswellia gum on a

1500 year old site (Qasr Ibrimin) as well as from

inscriptions on the tomb of queen Hathsepsut who

apparently used frankincense in the ‘kohl’ that was

apllied as eyeliner.

Many

other medicinal and traditional uses are ascribed to

frankincense. It would be impossible to name all of the

recorded uses, but some of the more interesting ones

have to be mentioned.

The

ancient world believed that incense carried prayers to

heaven. Thus it was used in many different religious

ceremonies. Frankincense was used to embalm corpses.

When the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamon was opened in 1922,

one of the sealed flasks released a perceptible whiff of

the incense, after 3000 years! During the funeral of

Roman emperor Sulla an entire statue was made from

frankincense and cinnamon. The annual consumption of

incense at the temple of Baal at Babylon was 2.5 tons.

Herodotus reported: “1000 talents of weight was offered

every year during the feast of Bel on the great altar of

his temple…”

Medicinally it was used by Pliny the elder as an

antidote for hemlock poisoning, while the Iranian

physician Avicenna though it was good for tumors and

fevers as well as dysentery. (Pliny also mentioned that

control of the frankincense trade had made the south

Arabians the richest people on earth).

Discoroides describes that bark of the frankincense tree

can be put into water to attract fish into nets and

traps. Chinese texts of the 12th and 13th century AD

mention 13 different kinds of frankincense used in

medicinal recipes. As late as 1868 the official

Pharmacopeia of India mentions that frankincense can be

used in the treatment of chronic pulmonary conditions

and as an ointment for carbuncles and ulcerations.

Till

today the Dhofari people put frankincense to use both as

medicine and as a beauty treatment:

The

gum is chewed to strengthen teeth and gums as well as

remove mucus from the head. Small pieces of gum are

mixed with salt and inserted into painful hollow teeth.

The smoke from burning gum is considered beneficial for

both man and animals. It is inhaled by people suffering

from headaches. Gum is an ingredient in eyewashes,

dissolves in milk to treat cough, and mixed with wine to

use as a sedative for children and a tranquillizer for

both women in childbirth and those about to be executed.

The bark, dried and powdered is made into a paste to

treat sores and muscle pain, and taken as a stimulating

and cleansing infusion. Fruits and leaves are used as

animal fodder and as a digestive tonic.

The

most well-known use of frankincense is as a fragrance.

The traditional Arabic use is in special incense burner

that are either wafted around the face, or passed

underneath head dresses or clothes, or placed underneath

wooden fumigating tripods to perfume and fumigate

clothing. Distilled extracted essential oils are used in

perfumes such as the famous Omani perfume “Amouage”.

Together with spices and ammonium salts it is also a

component of a special talcum powder to soften the skin.

A

very special grade of frankincense is used for the Quran

recitations of children. Some frankincense pearls are

soaked overnight in water with iron. The child to be

examined drinks the liquid first thing in the morning -

this should improve memory and the chance of success.

An

unusual application is to make long-burning tapers with

a mixture of pitch, sulphur, tow, pinewood sawdust and

powdered frankincense. With these long-burning torches

the dwellings of enemies were set aflame during tribal

wars. More peaceful uses consisted of rinsing old water

skins with frankincense bark and of dyeing cloth and

tanning leather with the bark to a popular mahogany-red

colour, as well as patching broken vessels with the

pliable gum.

From

these few examples we can have a glimpse of a way of

life that is still preserved to a certain extent but is

in danger of passing away. The care and consideration

for the different traditions that surrounded the use of

frankincense are time consuming by modern standards and

thus this traditional heritage is gradually lost.

|