|

Even

though food is an essential part of people's lives, not

much attention is paid to food as an important component

of a nation's heritage and folklore.

Nevertheless,

food has had a defining role in the culture of the UAE.

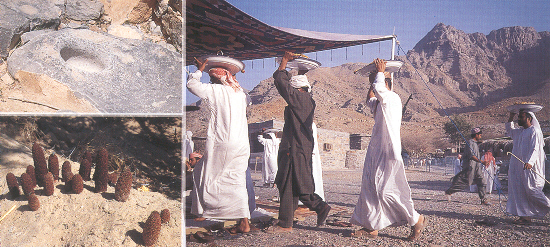

Special events such as weddings are celebrated with

traditional food and other cultural features, while food

also plays a functional role in religion. In fact a

major change in the food culture of the Arabian region

occurred when Islam reached here in the 7th

Century.

What we know of

people's daily lives before that time has mainly been

discovered through archaeological research. The earliest

people lived predominantly along the coast and ate fish

and shellfish. Large shell middens found along the Gulf

coast are witness to this fact. At times these early men

made forays to the inland plains to hunt for gazelles,

hared and reptiles. In recent archaeological digs in

Suffouh 2 (within the boundaries of Internet City)

evidence was found of the large-scale slaughter of an

early species of camel, as well as of oryx and gazelles.

Grains, in the

form of wheat, barley and sorghum, were already a food

as long as 7000 years ago. These were made into porridge

or ground to flour for making breads. The "tanur" ovens

of the type that are still being used nowadays, have

been excavated in several prehistoric sites in the UAE.

The bread that was made in those days must have been

prepared mainly from wild grains.

From the Hijra (7th

Century) up until 1960 (when oil became important) there

are written and oral records of the local food culture.

In the early nomadic days wheat was used to make

unleavened bread ('abud) with a minimum of water (a

precious commodity in desert life) and this bread was

cooked in the embers of the campfire. Famous UAE dishes

such as harees and aseeda also make use of wheat and

wheat flour and date back to this time. During this

period the daily activities of the majority of the

people centered on the provision and processing of food.

Subsistence occupations were herding of camels, sheep

and goats, tending date gardens and small vegetable

plantations, fishing and fish drying. More and more

trades cam into existence: the pearl trade, charcoal

burning, dhow building and copper works. For the export

of locally produced goods overland camel routes

developed as well as overseas trading in dhows.

Accounts of the

life of the bedouin of the desert were few and far

between. The earliest Western visitor was a Bolognese

adventurer, Ludovico di Varthema, who joined a haj

caravan in 1503 and reached Yemen. The first scientific

expedition was a Danish one in 1762, of which only one

person of the six scientists survived. Carsten Niebuhr

published his account of the ill-fated Arabia felix

expedition ten years later. In this book the first

detailed description of coffee cultivation appears.

Coffee from Yemen was traded mainly from Aden and Mocha

to the coffee houses of Europe. However, in Arabia

coffee was already used much longer, as a coffee bean

dated to be 1000 years old was recently found at

archaeological digs in Kush, near Ras la Khaymah.

Charles Doughty, traveling in 1876-1868 provided a more

detailed account of the daily lives of the desert

bedouin. The first crossing of the Rub al Khali (the

Empty Quarter) was by Bertram Thomas in 1931, followed

some twenty years later by the travels of Wilfred

Thesiger.

Some travelers

reported lavish meals, where the rules of hospitality

had obviously influenced the host to serve

extra-ordinary meals. Doughty, Bertram and Thesiger who

traveled with small parties of bedouin report much more

basic and monotonous food. The main meal was taken in

the evening after the milking. During traveling days

they ate 'abud, the unleavened bread that was cooked in

the fires. During rest periods in tribal encampments

large quantities of unleavened bread (shirak or rukak)

would be cooked on a saj – a convex metal sheet - over a

fire. If small game had been hunted for meat, this would

be thrown on the fire, skin and all, but if a beast was

slaughtered for a special occasion it would be cooked in

a large stewpot (jidda). In early days this was served

with wheat, but when rice became available through

import, this was preferred. As snacks during the rest of

the day a few dates and some camel milk was all that was

available. Dates (tamr) were very important for survival

in the desert. They were readily available in every

oasis, were easy to consume, unperishable, and

economical to transport. They were also nutritious camel

fodder. The bedouin made a special preserve of flour,

dried dates and clarified butter (samn), heated together

and kneaded into a solid mass. This ba-theeth was easy

to carry and kept well on long journeys.

Samn was prepared

by churning fresh goat or sheep's milk in a skin which

was inflated by blowing into it at regular intervals.

The fresh butter (zibdeh) was heated with flour and

spices. The samn was then stored in goatskins for

commercial use and in the skin of the dhub (Spiny-tailed

agame) for their own use. It was a major commercial

product of the bedouin herdsmen and was sold to provide

them with money to buy the staples they needed. These

staples included, besides dates, flour, wheat and rice.

Another milk product was yoghurt (laban) which was

salted and drained to make mereesy or jamid. Soon after

making it still resembled cheese, but after a while it

would become rock-hard, and could be nibbled as a

traveller's food or reconstituted with water after

having been ground into a powder.

Travelling in a

hot, dry climate the bedouin needed fluids to replace

what they lost during their exertions. Water was

precious and often of poor quality. Only after sporadic

heavy rains would a wadi flow and leave a few puddles

remaining for some days. Wells or permanent water holes

were deep, often up to 60 feet, and it was difficult to

haul the water to the surface. If a large camel herd

had to be watered, the bedouin would work in relays for

many hours. The waiting camels would urinate around the

wells and contaminate the water.

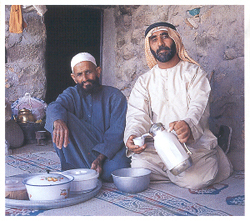

The social drink

of the Bedouin was coffee, qahwa. Green coffee beans

were always freshly roasted in a mahmas (roasting

spoon). The roast beans would be cooled in a wooden

tray. In some bedouin families the coffee was brewed in

a clay medlah. It would be transferred to the classic

beaked Arabian coffee pot of tinned copper or brass,

called dalla and served in small ceramic cups, finjaan.

It was often flavoured with cardamom.

Another source of

fluids was milk, haleeb. The nomadic Bedouin could

choose between the milk from camels, goats or sheep. The

first was much preferred and considered healthier, while

the other two were used mainly to make butter and

cheese. Camel milk has since been extensively researched

and found to have medicinal properties (a remedy for

diabetes and very high in vitamin C) besides its

important nutritional value. The milk diet was however

not satisfying in some respects; bedouin complained to

the explorer Doughty and begged him for "Damascus kaak

(biscuit), it is six weeks since I have chewed

anything".

Tea drinking was

introduced at a relatively late stage. Doughty may be

held responsible in part for its introduction as he

carried supplies for his own consumption and several

times offered it to bedouin who had not tasted it

before.

Bedouin existence

depended on their herds and flocks. The camel was the

supreme possession providing transport for man, milk for

food and drink, meat, hair and hides and dung for fuel.

Camels were wealth and would rarely be slaughtered for

meat. Any camel meat usually came from the slaughter of

surplus bull calves or injured or sick beasts.

Goats and sheep

could only be kept where water was available. They were

kept primarily for milk and meat and also skins, hair

and wool to make woven goods. The milk was mainly made

into samn.

Given the

meatless monotony of the day-to-day meals, it is no

surprise that an occasional hare or dhub was considered

a delicacy. Hares and more rarely gazelles were hunted

with both falcons and saluki dogs. The sandfish or skink

that occurs in large numbers on sand dunes could be

caught during their early morning sunbath, and was a

popular addition to the diet. As late as the early

1980's I was invited to such a skink feast, when I had

been found with my car stuck in the sand.

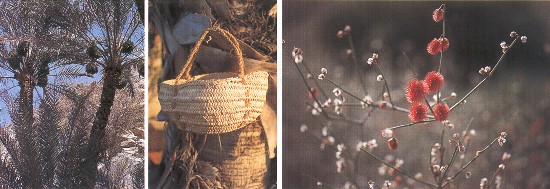

The nomadic bedouin rarely had access

to food of plant origin. Although there are many

different species of plants in the desert, the Bedouin

only used a few for food. There are several plants which

have water storage capabilities in the roots. The roots

of others, such as the Red thumb Cynomorion

coccineum, were savoured as a kind of aspargaus.

The desert truffle, faga, was also harvested and eaten

on the relatively rare occasions when they appeared

after early winter rains. Many plants were known to have

medicinal or veterinary value and these were often

collected. Calligonum comosum or "arta"

was a plant that had many uses. The wood was used for

fires, the young shoots as a salad green and the bright

red fruits provided a spice for rice. The ubiquitous

Asphodel lily was used to make dried cakes of

boiled curdled milk (iqt), while the whole plant, boiled

in water was used as a laxative. The two species of

sorrel that occur in the Emirates were always collected

as a vitamin C-rich salad green.

It was only when

local people visited the oasis that they could obtain

good dates and other fruits such as the nabak, the fruit

of the sidr tree (Zizyphus spina-christi).

Of course the people living in

the mountains had easier access to fruit and vegetables,

while those on the coast had a great variety of fish and

sometimes dugong or turtle meat in their diet.

Although in recent times the

residents of the Emirates have had access to an enormous

selection of imported foods, some of the old traditional

foods are still being prepared regularly.

Traditional

breads in the UAE are interesting. There are sweet and

savoury forms: khamis, logaimat, regagg, and mahalah to

name but a few. Unfortunately these traditional breads

are in danger of disappearing because they are replaced

by processed bread from supermarkets, or by khubz from

immigrant artisans. Only a few of the older people still

know the old bread making techniques, and young people

living in a more hurried world do not have the patience

to make their own bread. The same goes for some of the

wheat and date dishes mentioned above.

However the food

traditions can be kept alive by those who are

interested, since many of the old recipes have been

collected and published in athe "Complete United Arab

Emirates Cookbook" by Celia Ann Brock-Al Ansari. They

can also be obtained from the website:

www.uaeforever.company/dishes.

Some old recipes

adapted to this day and age (from the Complete UAE

Cookbook by C.A. Al ansari

REGAGG BREAD

Regagg (from

ragga meaning thin and delicate) bread is made daily

during Ramadan. It is also a popular winter-time bread,

eaten fresh and warm from the griddle with oil drizzled

over, then folded into pieces and eaten with fresh

honey.

4 cups

whole-wheat flour

1 1/2 teaspoons salt

water (tepid from tap)

Put flour and

salt in a large bowl, slowly start adding the water and

make a thick dough. Knead well. When the dough has lost

much of its elasticity, work in around 1 cup more water

at the end to make the dough slightly soft, yet pliable.

Cover with a wet cloth and leave for 12 hours.

Use a thick, ungreased iron or aluminum tortilla griddle

for cooking the bread over the heat. Once it is hot,

take a bowl of water, dip your hand in the water, then

take a ball of dough. Place it on the outer edge of the

griddle, then gently push it around the whole surface in

a circular fashion, with a metal spatula or the side of

your hand. Put any dough which drops off in the center

of the griddle back into the bowl for the next bread to

be baked.

Once the outer edges are slightly golden, the bread is cooked. Remove

from griddle with a spatula or blunt end of a knife.

BA-THEETH ~ Date crumple

An Arab favourite, this dish is from the UAE and is served

regularly with qahwa (Arabian coffee).

4 cups

wheat flour

2 3/4 cups seh - ripe sticky dates

1 teaspoon cardamom

1 1/4 cups toasted sesame seeds

3/4 cup samn (rendered butter)

Brown the flour

in a skillet, stirring to avoid burning. Stone the dates

and pull them apart with your hand. Place in a large

mixing bowl and sprinkle the cardamom and sesame seeds

over. Gradually add the samn and browned flour, a little

at a time, working the ingredients in with the

fingertips.

When all is well blended, the mixture should resemble large biscuit

crumbs. The mixture will keep for a week. |