The first time I found a fossilised sea

urchin, I thought it was a camel dropping

lying in the rubble. But then I noticed

five petal shapes on the round surface,

which I recognised from contemporary sea

urchins. Even though my first fossil sea

urchin was not a very good specimen, I was

delighted to hold something that was alive

65 million years ago!

At the time I had been in the Emirates for

just a few months and I had no idea how

rich in fossils this area is. Over time I

picked up fossils to which I gave names

such as Potato Chip, Shark Tooth, Spring

Roll and Little Lid. Gradually I learned

their proper names. The Potato Chip found

on Jebel Hafeet was a ‘nummulite’,

a one-celled organism akin to the

present-day amoebae. Shark Teeth were in

fact a kind of coral, belonging to the

Rudists and officially called ‘biradiolata’.

Spring Rolls, found on Jebel Buhays, had

the lovely but difficult name of ‘actaeonellid’ and the Little Lids were solitary corals called ‘cyclolites’.

My collection of whelks and turrets

(gastropods), cockles and scallops

(bivalves) grew, but sea urchins were

rare. I did not even know ammonites

existed here, until I heard someone

mention that he had found a straight

ammonite. Even though I was a complete

ignoramus about fossils, I did know that

ammonites are important in geology and

paleontology, because they help to date

the area in which they are found.

Ammonites are related to the present day

Nautilus shell, a curled snail. A straight

ammonite is partially or totally uncurled.

One day a friend took me to a new site

where she said she had found several sea

urchins. As we were searching the rubble

between the boulders, we picked up few

really nice specimens, as well as various

gastropods and other fossils. Then an

interesting shape, still half hidden in a

rock, caught my attention. I called

to my friend: “Come look at this

enormous snail. Don’t you think it looks

like an ammonite?”

Surely it couldn’t be one! It was the

size of large dinner plate, and if it was

indeed an ammonite, it would be an

extraordinary find. We took pictures and

consulted our local fossil expert, Mrs

Valerie Chalmers. And yes, it appeared to

be an ammonite.

When we heard that a natural history

expert from the British Museum was coming

to the UAE, we contacted him and proposed

to visit the site. He was a sea-urchin

specialist, but he was easily persuaded to

come look at something outside his field.

So on a day late in April we set out to

show him the area.

Dr Andrew Smith looked not at all as I had

expected. To my mind a fossil expert from

a venerable institution like the British

Museum should be middle-aged with wispy

gray hair and half moon spectacles.

Andrew, with beard, hat and backpack,

charging up slopes like a mountain goat,

did not conform to that image, but when he

started to explain fossils to us, his

expertise was immediately apparent.

In order to become an expert in matters

concerning marine fossils, Andrew studied

both geology and marine zoology. Of all

the many creatures that live in the sea,

he chose to concentrate on sea urchins,

officially called echinoderms. He told us

that there are 1700 species of echinoderms

known to man, of which a few hundred have

died out and are now known only as

fossils.

Echinoderms include starfish and brittle

stars, and they almost always have a

five-sided symmetry. In sea urchins, the

internal skeleton, composed of calcite

plates, is shaped like a rounded or

disc-shaped shell. The living animals have

tubular extensions with which they feed,

move and breathe. The number, size and

shape of these tubes can be recognised in

the fossilised echinoderm as sequences of

pores in specific configurations. These

pores, and the shape of the plates of the

shell, help to identify the different

species. In the UAE more than 30 different

species of fossilised sea urchins have

been found to date, some new to science

till just a few years ago. One is named

after the collector - the friend who had

shown me the site where the ammonite was

found.

As we walked around the site, Andrew

pointed out the greenish-black lava (ophiolites)

that used to be at the bottom of the Sea

of Tethys. During the so-called Cretaceous

Period, between 115 to 70 millions years

ago, the creatures that lived on the

bottom of the sea die there, were covered

with sand and debris and turned into stone

due to the enormous pressures that were

exerted. Then, volcanic activity in the

middle of the Sea of Tethys caused the

ocean floor to break up, spread and rise.

Some of the volcanic rocks were pushed up

on top of the Arabian landmass. These

became our present day Hajar Mountains.

The beaches that adjoined the ocean were

folded and pushed up also, carrying the

marine fossils along till they came to

rest along the western side of the Hajar.

Translated to present day geology, the

Limestone Mountains that rise from the

alluvial plains at the western edge of the

Hajar Mountains are the places where you

can find marine fossils.

Andrew showed how each layer of the marine

deposits was characterised by the animals

that used to live in it. As we climbed the

mountains he pointed out where the sea

became more and more shallow, until

finally we reached rocks that showed marks

of rainwater forming gullies, indicating

that now we were above sea-level.

It would probably have been easier to

recognize and understand if all the layers

were still in the sequence in which they

had been deposited. But the enormous

powers that pushed up the ocean floor and

crumpled the beaches had turned things

sideways and upside down, so that it was

difficult to visualise how things used to

fit together. However, it was no problem

to Andrew, who came back after a foray to

the top of the hill and said: “OK, now I

know where everything is, so I’ll be

able to tell where any fossil we find

belongs.”

As we trudged along Andrew explained that

there are several different types of sea

urchins. There are raspers that eat algae

from the rocks. There are sifters that

sift the debris in search of edible

particles, and there are selective sifters

that look for specific food among the

debris they sift.

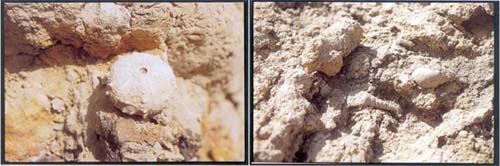

As we walked under an overhang where

recent rains had washed superficial layers

away, exposing fossils below, Andrew

pointed to a large fossil high up, out of

reach. It was a hand-sized sea urchin with

a rather thin skeleton that was already

being eroded. A bit lower down, he found

one belonging to a smaller species, which

he knocked out of the rock with one deft

blow of his geological hammer.

As he turned it around in his hand to look

at the lower side of the sea urchin, he

exclaimed: “Look, here are the tube

feet, still attached.” That meant that

the animal was alive and feeding on the

ocean floor when it was buried in the mud

of some prehistoric upheaval. The tube

feet were visible as white crystal-like

stripes, scattered along the edges of the

urchin.

Andrew moved slowly along the wall, in the

shadow of the overhang. Suddenly he

exclaimed:

“Now this is what I call a

sweetie”. Carefully he removed a small

sea urchin from its place in the rock. He

pointed out the pores and said that, with

a magnifying glass, we would be able to

see lines like the grooves on our

fingertips on the plates between the

petals. I offered him the magnifying glass

that I always carry for plant

identifications. As he studied the little

fossil, he became even more excited. What

should have been lines appeared to be dots

– and this made it a special find. “A

new genus and a new species”, he said. I

asked him how he could be so sure so

quickly. The answer was simple –

provided you had a lot of knowledge and

experience: “I know what family it

belongs to and there are only two species

in that family. Since it is neither of

those two, it has to be a new species”.

In fact, later on during his visit,

several more new urchins were found,

increasing the number of species known

from the Emirates considerably.

By now it was getting quite hot and we

still wanted to show Andrew “my”

ammonite. We climbed down to the rock that

contained it and as he caught sight is the

fossil, Andrew chuckled happily. “That

is a nice ammonite”.

The ammonite would help date the area and

Andrew suggested that I “donate it to

the Queen” - meaning it would go to the

British Museum where it would stay with

the collections form this area. (This

collection later formed a special exhibit

in the Biritsh Museum.)

But first it had to be removed from its

rocky embrace. It would be impossible to

get it out in one piece, as we could

already see that it had cracked in various

places. Andrew knocked a piece of rock

off, exposing the inner coil of the

fossil.

”You have to create an island”,

he said as he started the process quite a

distance away from the fossil. It was hard

and hot work and there was not much we

could do to help.

As we stood watching, Mrs Chalmers told me

that the Ras al Khaymah museum has a

picture of one large ammonite like this,

which was found on a remote site in the

mountains. I was chuffed at finding such a

nice specimen – and my very fist

ammonite as well. Beginner’s luck!

Little by little the fossil came out.

Andrew marked each new breaking surface

with letters, saying that he was going to

enjoy putting the puzzle back together in

London.

Just before leaving my friend noticed a

small sea urchin lying only a few feet

away from the ammonite rock. It was a

perfect specimen of a spectacular

sea-urchin fossil called Goniopygis

superbus. For her it was a good

compensation for not having found the

ammonite. I needed nothing to take home

– I was more than pleased at just the

idea of having found one of the two

largest ammonites in the Emirates. It was

later identified in the British Museum

(Natural History) by Dr. Mike Howarth as Pachydiscus

cf. jacquoti

(Seunes). It pieced together moderately

well, though the middle is not preserved,

i.e. it was not present in the original

specimen. One of these days I want to go

and visit it in London…

Fossils

can be enjoyed and studied at several

natural history exhibits in the country:

-

At the Natural History Museum, Desert

Park, Sharjah

-

At the natural history exhibit in the Abu

Dhabi Centre for Documentation

And

at the soon to open Children’s Museum at

the Creek Park in Dubai. The latter (part

of my collection) includes many of the

fossils mentioned in this article.

|