|

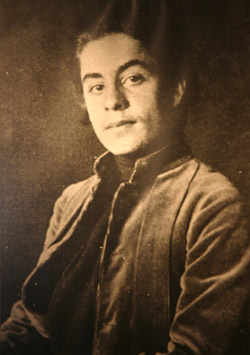

In the way that the late Mahmoud Darwish used his poetry to

express the struggle and suffering of the Palestinian people,

another great Arab poet used his literary gifts to heal the

hearts and minds of ordinary people seeking a balm for everyday

pains and help negotiate the obstacle course we call life. It

has been 77 years since Khalil Gibran drew his last breath but

through his works he enjoys rare immortality.

How did one person embrace so much wisdom? This is the question

asked by millions who still revere Lebanon’s best-loved

philosopher, writer and poet, who remained unmarried and

childless until the day he died.

How did a man who barely received any formal education in his

youth due to his family’s poverty, take possession of such

complex languages as Arabic and English and use them so expertly

as tools to express the depth of his insights?

Only the writings of the English bard William Shakespeare and

the Chinese philosopher Lao Tse surpass Gibran in terms of

readership, which means Gibran’s messages imparting the meaning

of love, marriage, friendship, freedom, work, pain, joy, sorrow

and passing resonate in our subconscious minds.

Amazingly, his advice is not only beautifully framed but many

contemporary psychologists would agree, it is also therapeutic.

For example, rather than echo the sentimentally of two becoming

one during marriage, in the Prophet he writes:

“But let there be spaces in your togetherness,And let the winds of theheavens dance between you.Love one another but make not a bond of love;

Let it rather be a moving sea between the shores of your souls.

Joy and sorrow are two sides of the same entity, he writes:

“Some of you say, ‘Joy is greater than sorrow’, and others say,

‘Nay, sorrow is the greater’.

But I say unto you, they are inseparable.

Together they come, and when one sits alone with you at your

board,

Remember that the other is asleep upon your bed.

Further, he admonishes us not be upset when we are separated

from a friend:

“When you part from your friend, you grieve not;

For that which you love most in him may be clearer in his

absence, as the mountain to the climber is clearer from the

plain”.

He describes “evil” as “good tortured by its own hungry and

thirst”; “beauty” as “eternity gazing as itself in the mirror”;

“giving” as “life that gives unto life – while you, who deem

yourself a giver, are but a witness”. He tells us to view our

“house” as “a mast” rather than “an anchor” and “not to dwell in

tombs made by the dead for the living”.

Each of us must interpret Gibran in our own way according to our

own parameters. But to me, he speaks of personal freedom, of the

need to let go of worn-out concepts, and the mistakes people

make striving to find their own inner security in people or

things.

A personal favourite quote deals with boundaries within

marriage:

“Give your hearts, but not into each other’s keeping.

For only the hand of Life can contain your hearts.

And stand together, yet not too near together:

For the pillars of the temple stand apart,

And the oak tree and the cypress grow not in each other’s

shadow”.

Gibran’s best-known work is “The Prophet”, which has dominated

the best-selling lists ever since it was first published in 1920

and has been translated into 26 languages.

Born Gibran Khalil Gibran bin Mikhael bin Saad, his English

teacher in the US anglicised his name to Khalil Gibran. Soon

after, at the age of 12, he emigrated to New York with his

mother, half-brother and two younger sisters.

While his alcoholic father remained in the northern Lebanese

town of Bsharri, (then part of Syria), his mother was forced to

become a door-to-door saleswoman to survive until she managed to

save enough to open a dry goods store.

At the age of 15, he returned to Lebanon to pursue his studies

and after co-founding a college literary magazine, he was

elected ‘College Poet’. Just weeks before his return to Boston

in 1902, tragedy struck; his sister died of tuberculosis and a

year later his brother’s young life was similarly cut short,

while his mother died after being ravaged by cancer.

Perhaps it was these terrible losses that afflicted his young

existence that gave him an insight into the futility of trying

to hang onto those we love.

His family decimated by disease, the most important people in

Gibran’s life, apart from his surviving sister Mariana, were an

American school mistress Mary Elizabeth Haskell ten years his

senior and the Lebanese artist Youssef Howayek, with whom he

studied, (and became a lifelong friend of), in Paris under

Auguste Rodin.

Gibran’s relationship with Mary – generally believed to have

been platonic, although emotive – was complex as can be seen

from their letters; extracts of which have been published. It is

known that Mary Haskell became his editor and patron,

facilitating his studies in Paris and enabling him to

concentrate on his artistic and literary pursuits.

On April 10, 1931, Gibran succumbed to TB and cirrhosis of the

liver, leaving his studio and its contents to Mary Haskell and

his book royalties to his hometown Bsharri. In his Will, he

asked to be buried in his beloved Lebanon.

|

|

The Palestinian poet Salma Khadra

Jayyusi once wrote that Gibran’s “vision of a world made sterile

by dead mores and conventions” was “redeemable through love,

goodwill, and constructive action”.

It is because the spirit that still shines from his words is

uplifting and positive, his messages are as relevant today as

they were on the day he filled his pen with ink to so

beautifully enrich posterity and make his country proud.

|